Why every model sucks nowadays (and why it's good news)

OpenAI's Code Red, Google's Gemini dominance, and why model convergence is actually great news for enterprises. the real race isn't about which model is smartest—it's about integration.

GPT-5 in August. GPT-5.1 in November. GPT-5.2 in December. New image model yesterday.

OpenAI is shipping faster than ever—and the reviews keep saying the same thing.

"Underwhelming." "Mixed bag." "Rushed release stitched together on top of ambitious research milestones."

That's not a competitor talking. That's what users said about GPT-5.2, OpenAI's latest flagship model, released last week. One reviewer noted it "feels bland, refuses more, hedges more—like someone who just finished corporate compliance training and is scared to improvise."

Meanwhile, Google's Gemini 3 broke the LMArena leaderboard with a record 1501 Elo score. Marc Benioff, CEO of Salesforce, publicly announced he was ditching ChatGPT for Gemini. And Sam Altman responded by declaring an internal "Code Red"—the exact same alarm Google sounded three years ago when ChatGPT first launched.

The hunter has become the hunted.

But here's what most people are missing: this isn't a story about who's winning. It's a story about what happens when everyone hits the same ceiling. And why that ceiling might be the best thing that ever happened to enterprise AI.

The code red symmetry

Three years ago, Google panicked. ChatGPT had captured the world's imagination, and Sundar Pichai redirected teams across the company to respond. Engineers from Search, Trust and Safety, and Research were pulled into emergency AI development. The result was Bard, then Gemini, then the current Gemini 3.

Now the roles have reversed.

On December 2, 2025, Altman sent an internal memo telling OpenAI employees they were at "a critical time for ChatGPT." The company would delay advertising plans, pause work on shopping and health agents, and shelve improvements to their personal assistant feature. All hands on deck for the core product.

What followed was a blitz of releases. GPT-5.2 on December 11. A new image model, GPT Image 1.5, on December 16—reportedly accelerated from a planned January launch. OpenAI executives insisted to reporters that this wasn't a reaction to Gemini 3.

The timeline suggests otherwise.

August 2025: GPT-5 launches. Reviews call it "overdue, overhyped, and underwhelming." Gary Marcus writes that it was dubbed "Gary Marcus Day" for proving his criticisms correct.

November 12: GPT-5.1 releases—six days before Gemini 3.

November 18: Google launches Gemini 3. It immediately tops every major benchmark.

November 20: Google releases Nano Banana Pro, their image model built on Gemini 3. It goes viral. Google reports Gemini app users grew from 450 million to 650 million in three months.

December 2: Altman declares Code Red.

December 11: GPT-5.2 releases. Reviews are "mixed."

December 16: GPT Image 1.5 releases. Fortune's headline: "OpenAI releases new image model as it races to outpace Google's Nano Banana amid company Code Red."

Four major releases in four months. Each one reviewed as rushed, incremental, or underwhelming. This isn't the behaviour of a company leading the market. It's the behaviour of a company trying not to lose it.

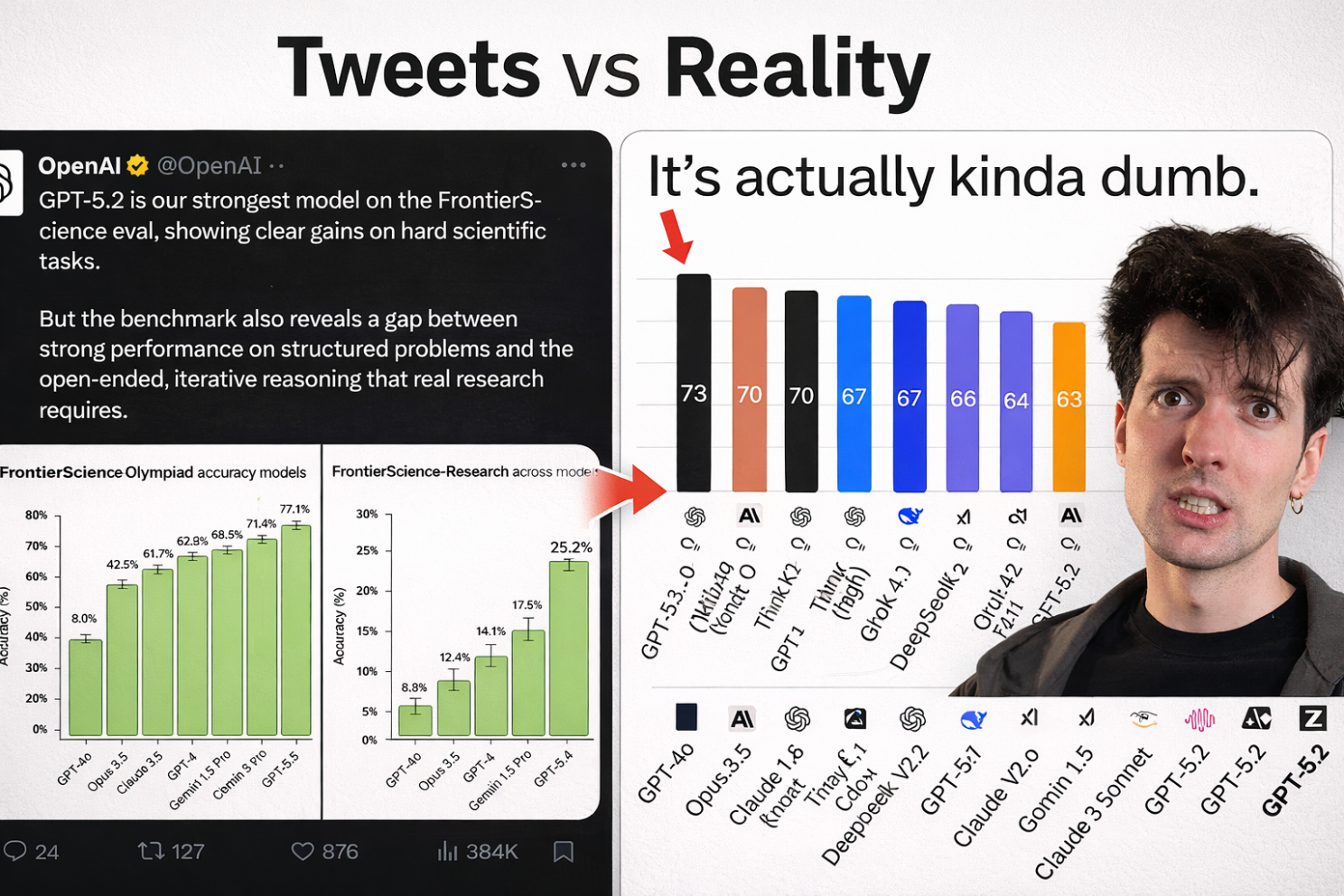

The paradox: better benchmarks, worse results

Here's what makes this strange. On paper, GPT-5.2 is better than any previous model. Higher scores on reasoning tests. Better performance on coding benchmarks. Improved long-context handling.

And yet users keep saying it feels worse.

This paradox has a name. Ilya Sutskever, OpenAI co-founder who left to start Safe Superintelligence, explained it in a November interview with Dwarkesh Patel:

"How to reconcile the fact that they are doing so well on evals? You look at the evals and you go, 'Those are pretty hard evals.' They are doing so well. But the economic impact seems to be dramatically behind."

His diagnosis is blunt: "These models somehow just generalize dramatically worse than people. It's super obvious."

Sutskever describes what he calls the "bug loop"—a pattern anyone who's used AI for real work will recognise:

"You tell the model, 'Can you please fix the bug?' And it says, 'Oh my God, you're so right. Let me go fix that.' And it introduces a second bug. Then you tell it about the second bug, and it says, 'Oh my God, how could I have done it?' And it introduces the first bug again."

The models ace the tests. They struggle with the work.

Why? Sutskever suspects benchmark overfitting:

"One thing you could do, and I think this is something that is done inadvertently, is that people take inspiration from the evals. You say, 'Hey, I would love our model to do really well when we release it. I want the evals to look great.'"

The Stanford AI Index 2025 confirms the pattern. Many benchmarks have become "saturated"—models score so high the tests are no longer useful for differentiation. This happened simultaneously across general knowledge, image reasoning, math, and coding.

We've been training models to ace tests, not to master skills.

The convergence: everyone hit the same wall

It's not just OpenAI.

Marc Andreessen said it plainly in a recent podcast: AI models "currently seem to be converging at the same ceiling on capabilities."

Sutskever agrees, but frames it differently: "The 2010s were the age of scaling. Now we're back in the age of wonder and discovery once again."

Translation: the strategy that got us here—make it bigger, train it longer, throw more compute at it—has stopped working. Everyone is hitting the same wall.

Look at the LMArena leaderboard. Gemini 3 Pro sits at 1501 Elo. Claude Opus 4.5 is close behind. GPT-5.2 is in the mix. The gaps between them? Single-digit percentages on most tasks. For practical purposes, they're interchangeable.

This is what maturation looks like.

When technologies are immature, leaders have massive advantages. Early cars were unreliable; owning one required a mechanic on staff. Early computers filled rooms; using one required specialised training. The leaders in those eras had capabilities others couldn't match.

When technologies mature, the gaps close. Cars became reliable enough that anyone could own one. Computers became simple enough that anyone could use one. The differentiation moved from "does it work?" to "how do you integrate it into your life?"

AI has reached that inflection point. The question is no longer "which model is smartest?" It's "how do you make any of them actually useful?"

The money: only one company can survive a war of attrition

There's another dimension to this convergence that matters enormously for anyone betting on AI vendors.

OpenAI will burn $115 billion through 2029. They're projecting $74 billion in operating losses in 2028 alone. The company spends $1.69 for every dollar of revenue it generates. They need to raise money constantly—and they need investors to keep believing the next model will be the breakthrough.

Google made $70 billion in profit last year. They have $98 billion in cash reserves. They own their own TPU chips, giving them a 4–6x cost advantage over competitors who rely on NVIDIA. They don't need to convince anyone of anything. They just need to keep executing.

When models converge and benchmarks saturate, the only remaining differentiator is sustainability.

OpenAI's bet is that they'll achieve some breakthrough—AGI, superintelligence, something transformative—before they run out of runway. Altman has said they're "past the event horizon." The fundraising pitch requires investors to believe this.

Google's bet is simpler: we can do this forever. They're not racing toward a breakthrough. They're building infrastructure for a long game.

If you're an enterprise choosing an AI vendor, this matters. OpenAI needs you to believe the next model will be dramatically better. Google just needs you to believe they'll still be here.

The exodus: when builders leave and sellers stay

There's a pattern that should concern anyone paying attention to OpenAI's trajectory.

The scientists who built these systems are leaving. The executives selling them are staying.

Ilya Sutskever, OpenAI co-founder and the architect of many of their breakthroughs, left in May 2024 to start Safe Superintelligence. In his November interview, he was explicit that scaling has hit a wall.

Yann LeCun, who built much of Meta's AI research capability over 12 years, announced he's leaving in November 2025. His position is even more stark: "Autoregressive LLMs are doomed… the probability of generating a correct response decreases exponentially with each token."

Geoffrey Hinton, the "godfather of deep learning," left Google in 2023 specifically to speak freely about AI's limitations and risks.

Mira Murati, OpenAI's CTO, left in 2024. Alec Radford, lead author on the original GPT paper, is gone too. Dozens of top researchers have departed for Anthropic, for Murati's new company Thinking Machines, for Meta's Superintelligence Labs.

When the people who understand the technology best choose to leave, that's not a personnel issue. It's a tell.

The researchers are saying, through their actions, that the current path has limits. The executives are saying, through their fundraising, that the breakthrough is imminent.

One of these groups understands how the technology actually works.

The real problem: the model was never the hard part

Here's the uncomfortable truth that neither OpenAI nor Google wants to emphasise: the model was never the bottleneck.

The MIT NANDA report found that 95% of GenAI pilots fail to deliver measurable P&L impact. S&P Global's 2025 survey showed 42% of companies abandoned most AI initiatives—up from 17% the year before. Gartner predicts over 40% of agentic AI projects will be cancelled by 2027.

These failures aren't happening because the models are bad. GPT-4 was extraordinary. Claude 3.5 was extraordinary. Gemini 2.5 was extraordinary. Companies had access to genuinely powerful AI.

They failed anyway.

Why? Because integration is hard. Workflow redesign is hard. Change management is hard. Getting AI to work reliably inside existing business processes, with existing data, alongside existing teams—that's the actual challenge.

McKinsey found that organisations reporting significant AI returns were twice as likely to have redesigned end-to-end workflows before selecting models. The model choice was secondary. The integration architecture was primary.

We've been staring at the engine while ignoring the car.

Why convergence is good news

This is where the narrative flips.

If you've been waiting for the "right" model to arrive before investing in AI, convergence should be liberating. The right model is already here. Several of them, actually. They're all good enough.

What convergence means:

- You can stop chasing releases. GPT-5, 5.1, 5.2—the differences are marginal for most enterprise use cases.

- You can build on a stable foundation. When technology is immature, you're building on sand. When it matures, you're building on bedrock.

- You're not hostage to one vendor. If Gemini, Claude, and GPT all perform similarly, you have leverage. You can switch. You can negotiate. You can build vendor-agnostic systems.

The focus shifts to where value actually lives. Not in the model. In the integration. In the workflow. In the process transformation.

The panic at OpenAI isn't your problem. It's their problem. They need the next model to be transformative to justify their burn rate. You don't. You just need models that work reliably—and you already have them.

The new race: from model selection to integration architecture

The model race is ending. A different race is beginning.

The winners of the next decade won't be the companies with the best models. They'll be the companies that figure out how to make AI work inside organisations.

This is a fundamentally different challenge. Model development is a research problem. Integration is an engineering and change management problem. The skills don't transfer. The approaches don't transfer. The timelines don't transfer.

Model improvement happens in labs over months. Integration happens in enterprises over years.

The companies that capture value from AI won't be watching benchmark leaderboards. They'll be doing the slow, unglamorous work of embedding AI into actual business processes, measuring actual outcomes, and iterating based on actual results.

This is where Sutskever's observation becomes actionable. The models seem smarter than their economic impact would imply. The economic impact comes from integration, not from intelligence.

Structure without intelligence is rigid automation. Intelligence without structure is unpredictable capability. The answer is both—and "both" lives in the integration layer, not the model layer.

The uncomfortable truth

I run an AI company. I've watched this convergence unfold. And I've bet everything on a specific hypothesis.

The economic impact of AI won't come from a model that magically does everything. It will come from deep, lengthy integration into enterprise processes and ways of working. This is slow. It's unglamorous. It requires understanding specific businesses, specific workflows, specific edge cases.

It's also where the actual value lives.

This is what we've built Nexus around. Not chasing the latest model release. Not promising that the next version will finally deliver. Instead: methodical integration work, tied to measurable ROI, across whatever models make sense for the task.

Every POC we run at Nexus is tied to actual business outcomes. Not benchmarks. Not demos. Revenue, conversion, cost reduction—metrics that show up in financial statements. When Orange Belgium built a customer onboarding workflow on Nexus, it wasn't because we had a better model than anyone else. It was because we helped them build a process that actually worked. It now generates $4M+ monthly with 50% conversion improvements.

That's not overnight success. It took work. It took iteration. It took understanding their specific business.

But that's the point. AI transformation isn't an overnight success. The vendors promising otherwise are selling a fantasy—one they need you to believe to justify their valuations and their burn rates.

The reality is slower and harder and more valuable: AI that's deeply embedded in how work actually gets done, improving outcomes that actually matter, built on a foundation stable enough to invest in.

The models have converged. The technology has matured. The question is no longer which model will win. It's who will do the integration work to make any of them transformative.

That's the real race now. And it's barely started.

Sources

- Fortune, The Wall Street Journal, The Information – OpenAI "Code Red" memo and internal strategy (December 2025)

- TechCrunch, Axios – GPT-5.2 release coverage and user reviews (December 2025)

- Google DeepMind Blog – Gemini 3 announcement and benchmarks (November 2025)

- Dwarkesh Patel Podcast – Ilya Sutskever interview on generalization paradox (November 2025)

- Medium user reviews – GPT-5.2 "rushed release" analysis (December 2025)

- VentureBeat – GPT-5.2 first impressions, mixed reception (December 2025)

- Gary Marcus Substack – GPT-5 criticism and "Gary Marcus Day" (August 2025)

- Stanford AI Index 2025 / IEEE Spectrum – Benchmark saturation analysis

- Fortune – OpenAI financial projections, $115B burn through 2029 (November 2025)

- TechScoop – Google vs OpenAI infrastructure cost comparison, TPU advantage

- Wikipedia, OpenAI Blog – GPT-5.1 release timeline (November 2025)

- CNBC – Nano Banana Pro launch and Gemini user growth (November 2025)

- MIT NANDA Report – 95% GenAI pilot failure rate (August 2025)

- S&P Global Market Intelligence 2025 – Enterprise AI initiative abandonment

- Gartner June 2025 – 40%+ agentic AI project cancellation prediction

- McKinsey 2025 AI Survey – Workflow redesign correlation with AI returns

- TechCrunch – Current AI scaling laws and diminishing returns (November 2024)

Your next

step is clear

The only enterprise platform where business teams transform their workflows into autonomous agents in days, not months.